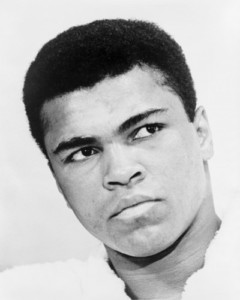

When I was growing up in Chicago in the 1960s, professional boxing was a big sport that my dad followed and heck, like a lot of kids, I enjoyed many of the things my parents did. My dad exposed me at a very young age to a gold-medal Olympic boxer named Cassius Clay, who would later changed his name to Muhammad Ali.

When I was growing up in Chicago in the 1960s, professional boxing was a big sport that my dad followed and heck, like a lot of kids, I enjoyed many of the things my parents did. My dad exposed me at a very young age to a gold-medal Olympic boxer named Cassius Clay, who would later changed his name to Muhammad Ali.

Ali was the classic showman who pontificated by using the most quotable quotes. That talent, mixed with a boxing acumen we had not seen before, made him a PR person’s dream, but his activities also made him an occasional PR person’s nightmare. He was in the mix of the turbulent 60s, and I vividly remember his charisma and cockiness: from when he announced his name change (denouncing his “slave” name) in the midst of the Civil Rights movement, to his arrest for evading the Vietnam War draft. This made Ali an incredible polarizing figure, buoyed by his braggadocios approach when the cameras came on. But in the end, it turned out that Ali’s taunts and beliefs were really nothing more than the truth. Time vindicated his actions. But through it all, Ali just didn’t talk the talk, he walked the walk with a confidence that was simply magnetizing.

Looking back

Full-disclosure: I was, am, and always will be a Muhammad Ali fan, so I write this with extreme prejudice. I kept a scrapbook as a kid, an old spiral-bound calendar planner with a red cover my dad has discarded, which I found the other day. Inside, I pasted an eclectic mix of newspaper photos: Apollo missions, photos of all the 1968 presidential candidates like Nixon, Humphrey and Wallace, Chicago Blackhawks legend-in-the-making Bobby Hull getting his mouth wired shut from a broken jaw while his young son looked on in sadness, and most importantly, photos of Ali and my other favorite boxer, ‘Smokin’ Joe Frazier, and the punishment his face took after beating Ali in March 1971 at Madison Square Garden.

The year before, my dad brought home something for my brother Eddie and I. Dad was the night manager at the old Continental Plaza on Michigan Avenue, a Westin hotel across from the Hancock Building (now called the Westin Michigan Avenue). He would meet many celebrities and even world leaders, checking them into their rooms on a regular basis, but he rarely asked for an autograph. This night he did. He handed us a “Front Card,” what bellman used to track check-ins and keep them in order, which was dated and time stamped by a machine. On the back, it said “Best Wishes Eddie & Kevin, Muhammad Ali.” I was thunderstruck. My dad has met Ali before, when he was Cassius Clay, but this time, it was more personal for me because the Champ had written my name.

Ali on Miami Beach

My family moved from Chicago the next year to South Florida, and my dad went to work at the Fontainebleau Hotel (later becoming a Hilton) and eventually became the Superintendent of Service (responsible for the service staff: bellman, valet, mailroom, baggage room, etc.). During one summer, I believe it was 1976, Ali spent a month with his entourage, living at the Fontainebleau and working out at the 5th Street Gym, owned by his trainer, Angelo Dundee. Ironically, one of his sparring partners was also a bellman at the Fontainebleau who worked for my dad, Levi Forte. Levi was one of my favorite co-workers and to think he boxed with The Greatest, and that as a fighter, he lasted 10 rounds with George Forman, more than any other boxer? Well, that made him a real giant in my eyes.

A lot of celebrities stayed at the Fontainebleau. My brother Jim, who took my dad’s place in management at the ‘Bleau after he retired, could write a book about his escapades checking in celebrities. My dad could have written a series of novels. Because in the hotel business, you see the side of celebrities others rarely see, such as who is a jerk (a majority, unfortunately) and who is genuinely nice and personable (not that many, again, unfortunately). Many hide out during their stay, traipsing through the lobby as only a means to get to their limo. Most would either avoid or limit signing autographs.

Ali was different, very different. He would often sit in the lobby on the circular bench that was backed by a mirrored column, wearing a casual shirt and slacks, with his feet resting on the beautiful Italian marble floors. And he would just hang out. No entourage, sitting in solitude. People would walk by and say ‘Hi,’ occasionally asking for an autograph, but generally left him alone. I had an unobstructed view as I was working as a messenger and hung out at the desk. I would say “Hello” when I would see him, or deliver a newspaper to his room, but never got up the never to actually talk to the Champ.

What Ail taught me

But what I observed that summer has stuck with me for decades. Here was a man who would become the most recognized face on the planet, who so many people loathed and so many others loved for his brash style and panache, simply being one of us. The ‘Greatest’ was one of the nicest, most understated, and yes, believe it or not, humble human beings.

This was not the Ali that turned it on when cameras were pointed in his direction. This was the Ali that would sit in the lobby of the hotel and shadow box a 5-year-old boy that ended with a big, embracing hug and a smile on the child’s face that would melt Ali’s harshest critic. I never, ever saw him turn away someone asking for an autograph. He was patient and kind, incredibly soft-spoken. When he smiled, it was instantly contagious. Watching him that summer, I was never more proud to be a fan of Ali.

For the years that followed, I often would chime in when someone mentioned his name. I just had to debunk that myth that he was a blowhard. That was for the cameras. His legend came from his real persona, his beliefs in humankind, with a focus on the last part of that word: kind.

That’s what Ali taught me above all else. The power of kindness: that no matter who you are or how important you think you are, you are always first and foremost really just like everyone else. Humility and kindness go hand and hand and there is no reason to be unpleasant or treat people as if they are somehow beneath you. The Greatest had one gift that people who interacted with him knew: He was a kind and genuinely caring person.

A final word

I shared a bit of my Ali s tory the other day with Randall “Randy” Standard, CEO of VoicePad, and a WAV Group Communications client. He lives in Ali’s hometown, Louisville, Kentucky. Randy shared with me his Ali story, which echoed the experience I had. Both of our interfaces with Ali left us with the same impression: he was the real deal.

tory the other day with Randall “Randy” Standard, CEO of VoicePad, and a WAV Group Communications client. He lives in Ali’s hometown, Louisville, Kentucky. Randy shared with me his Ali story, which echoed the experience I had. Both of our interfaces with Ali left us with the same impression: he was the real deal.

While his quotes – “Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee, his hands can’t hit what his eyes can’t see” or “I’m so fast that last night I turned off the light switch in my hotel room and got into bed before the room was dark” and of course, about the Frazier fight: “It will be a killer and a chiller and a thriller, when I get the gorilla in Manila” – will forever be embedded in my brain, the most poignant memory for me was watching him be something he said he wasn’t, but in reality he was humble. Now that lesson, being humble and kind, really was The Greatest.